|

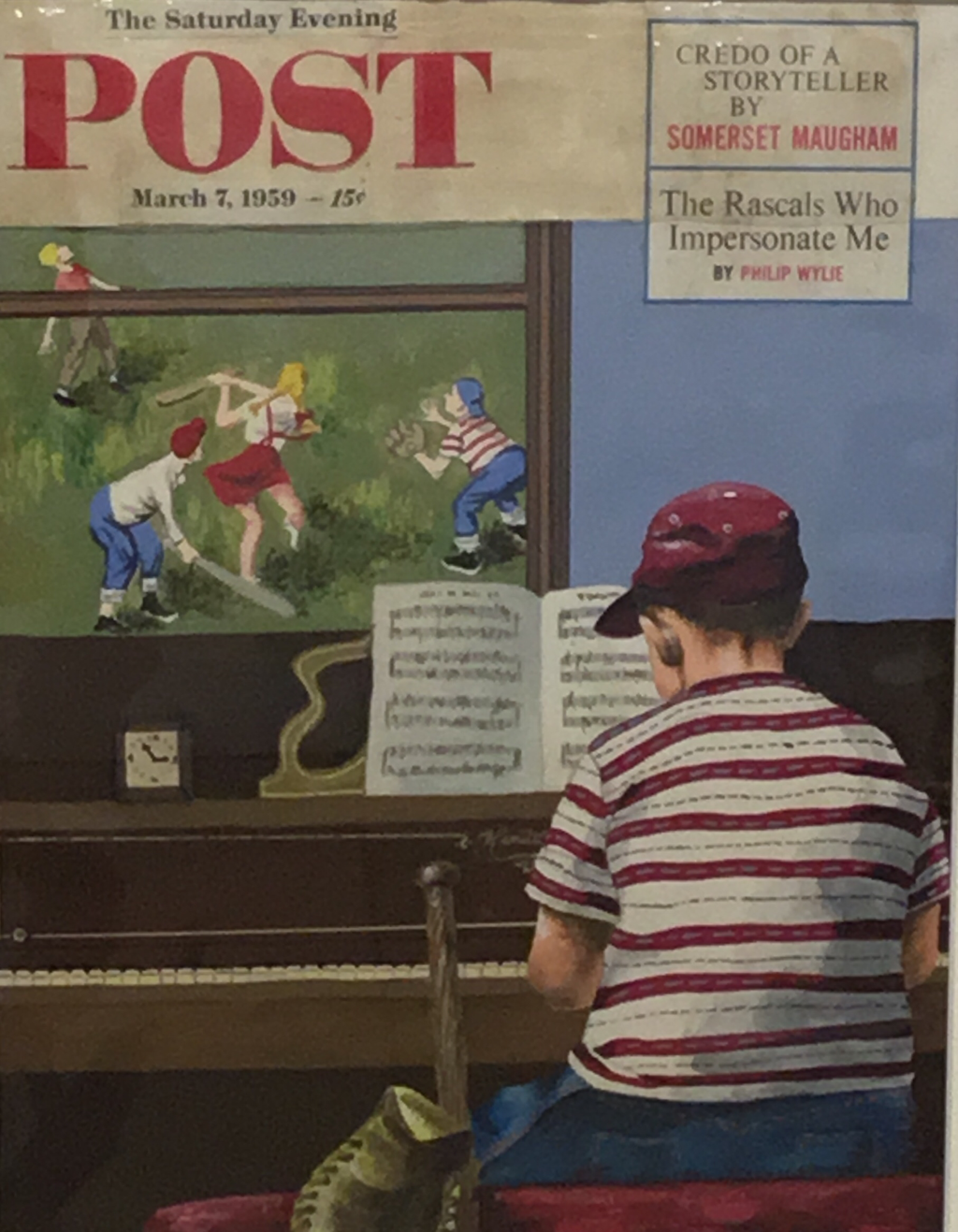

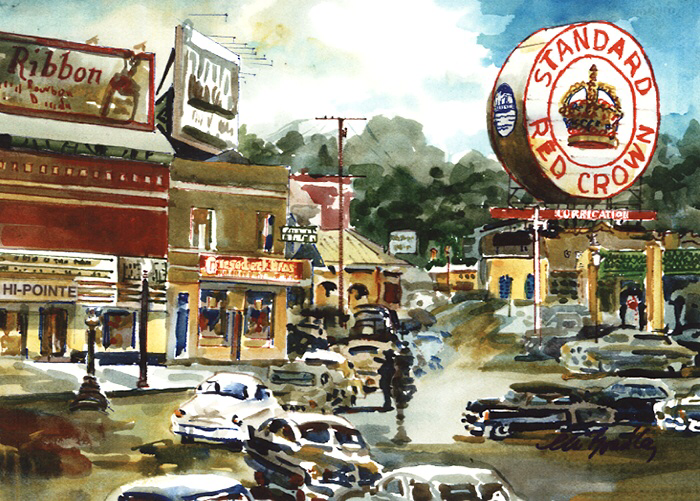

It’s not unusual to think of representational and abstract painting as stylistic opposites. But when we explore the range of styles and techniques that occupy those two worlds, the distinctions between them start to blur. We might even find ourselves concentrating less on whether we’re perceiving “real” objects in the paintings and more on how the artist chooses to interact with the viewer. And to what aim? Particularly when the objective is to elicit an emotional - or visceral - response of some kind. Allen Kriegshauser’s work - whether plein air landscapes, scenes of small towns, the human figure or still life - have a way of immediately capturing our attention - setting moods through his use of color, contrast and the ways he captures and depicts light. “Even though my paintings are figurative, I’m pushing the abstract,” he says. “When you walk into the room, I want my painting to be the center of attention. Color and contrast pull the eye.” And his paintings do command attention. Somehow you seeem to know how it feels to be in the places he depicts on the canvas. Then you want to look closer and see how he does it. Architectural details are suggested impressionistically. Colors that work quite well seem, upon closer examination, to be not quite what you might expect. And there’s this sense of light that makes you feel its presence - as if you can almost reach out and touch it. Through manipulation of color and contrast he improves upon reality as much as he captures it. His paintings reveal as much about how a scene feels as how it appears. He pursues his craft aggressively, participating in competitions and exhibitions around the country. And he’s happy to share his techniques in workshops. “What attracts me to a scene is high contrast - something that’s got heavy shadow that’s going to put that light in the painting from a value side. And then I reinforce it from the color side. I usually push my values, especially in the darks, at least two values steeper and my lights two values higher, so I get that pop.” He considers the colors he actually perceives before him in the moment to be more of a starting point - which he enhances with pigment until he feels he’s delivering a sense for the feel of the air, the time of day, and the various emotional reactions that are produced when natural light reveals itself on surfaces. “I’ve been frequently described as a high chroma painter, which means the colors are a little more on the artificial side. “I’ll start with the local color - the actual color you see - as my base and then push the chroma. And if I get bored with a painting or it just isn’t working, I’m not adverse to throwing an extreme color out there and exciting my eyes, which helps me correct that local color that isn’t working out.” Kriegshauser often posts on Facebook paintings he is in the process of creating - within the actual scene - to demonstrate his process of interpreting the natural world. An old black boot takes shape as a mix of colorful brush strokes - with blues, reds and yellows telling the story - midrange colors creating interesting shapes and shadows. Reaching beyond what the senses easily perceive to serve up what we might not quite see, but nevertheless feel. “But I don’t give the viewers everything. I make them work for some of it. So, I’ll paint a shadow, suggesting a window and have them figure out the rest.” By deciding what to include and what to withhold, he asks us to complete the creative experience by bringing our own experiences to the process. “I’m not a truist by any means. Why create when all you’re doing is duplicating?” And if I can get a response from someone, then I’ve done my job. Visit the art of Allen Kriegshauser at allenkriegshauser.com. It’s tempting to celebrate the eightieth birthday of a prolific and renowned artist by taking a look back at her life’s work. And that’s perfectly fine with Marilynne Bradley. But what she really wants to do is talk about what’s next. Bradley turns 80 on April 12, and you are invited to one big birthday bash that evening at the Webster Arts Galley at Eden Seminary, where her latest exhibition “Transitions” is on display. A brief summary of Bradley’s career is impossible. Highlights include years as a commercial artist, teacher and nationally acclaimed painter. She is a member of the Webster Groves arts commission and an active participant in a variety of arts non-profits. She teaches watercolor every Wednesday evening at the Green Door Gallery in Old Webster, where she also displays her work. Watercolor is her preferred medium, but she’s comfortable in a wide range of media and genre. (That’s her mural on the west wall of Schnarr’s Hardware.) She has produced books, participates in about 25 shows a year around the country, and has received more awards, honors and signature letters than she cares to talk about. This fall she’ll be displaying a collection of her latest works - which take a very different stylistic direction - at the St. Louis Artists’ Guild. Oh, and she was a child prodigy on the cello, which got her a music scholarship to Washington University, where she studied chemistry with plans to pursue a medical degree before deciding to try her hand at art. My apologies for leaving a lot out here. The woman defies labels. “Transitions” is the perfect title for her current exhibition, because it captures the essence of her artistic career. Every piece on display can be seen and appreciated for what it is - but also how it laid the foundation for the next stage of her art. From her early commercial work (including a cover of the Saturday Evening Post) to her loose and fluid watercolors to her architectural works and her latest graphic, linear paintings there is a continuity to the creative energy that flows through and transforms her art. Central to Bradley’s approach to art is her background as a commercial artist. Even when she experiments with techniques, there is a certain no-nonsense practicality that drives her. “Before I begin, I already know what I’ve planned. It’s in my head. You have to have an idea; you have to have a deadline. So consequently, I work very fast and I know exactly what it’s going to be before I start. “So I can paint just like it’s a job, but I also know how to put real feeling into a picture. So in some ways I’m on both sides of the fence.” Bradley is a representational artist. She is inspired by what she sees in the real world. “I see something, then all of a sudden I want to recreate it. That’s what I like. So what I’m trying to do is experiment. I’m always curious, and the curiosity takes me in so many different directions.” But when she attended Washington University in the late ‘50s, the kind of art she wanted to make was not the style of the day. “This was the time of abstract and conceptual art. You weren’t supposed to actually look at anything. It was all supposed to come out of your mind. It wasn’t for me. I didn’t enjoy it, so I went into advertising and illustration. That was real, and that’s what I needed - how to make a real painting that actually looked like something.” About two years ago she bean creating a series of paintings that seemed to take a new direction. It began with a painting of a stairway. She grew fascinated with the lines and the geometry and applied that focus to more of her paintings, including landscapes and cityscapes. And though many of her followers thought it was something totally new for her, she describes it as revisiting a technique she’d experimented with years earlier.” “The first year nobody liked them. That happens. It takes a while for people to accept change. It didn’t bother me. I was doing it for myself. But then they started getting into shows, and I’ve started getting some awards for them, so maybe I’m going in a good direction. I’ll keep doing it until I get pulled in another direction.” Her advice to young artists is simple. “You need to paint every day, because what you’re doing is training your eye to see. So you come to see even the most trivial things in new ways. You see patterns in them rather than them just being objects. And they become pieces of art.” So, for Marilynne Bradley, this milestone year is a chance to celebrate with friends and rediscover works from her archives. But beyond reflecting on what she has done and where she has been, the fun for her is showing how every step and every direction she’s taken over the years has laid the groundwork for the next chapter. Transitions. And all the celebrations aren’t going to interrupt her work, because she’s got a lot more to do. “It’s curiosity that keeps me from getting stale and doing the same thing over and over again. Everything I do evolves into something else. Years ago I came to this point in my life when I thought, all right, I’ve come this far, it’s time to do whatever I want to do. I might never have another chance. Whatever comes by, I’m going to do it.” You can see more of Marilynne Bradley’s work in her books, Once Upon a Time in St. Louis and St. Louis Watercolor: The Architecture of a City as well as at Green Door Gallery and on her website, marilynnebradley.com.

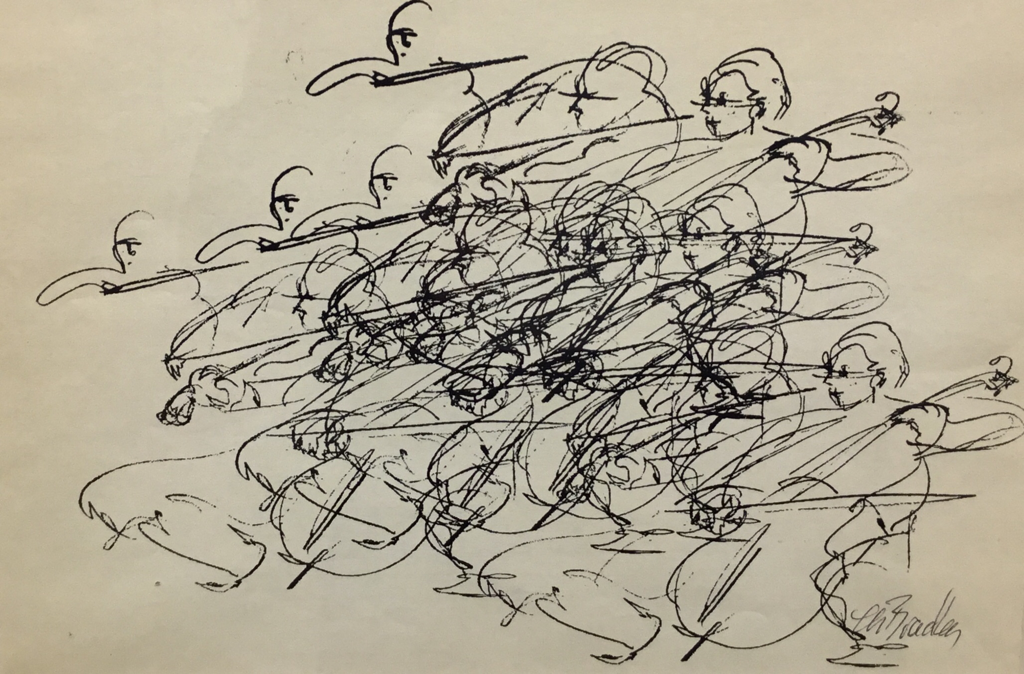

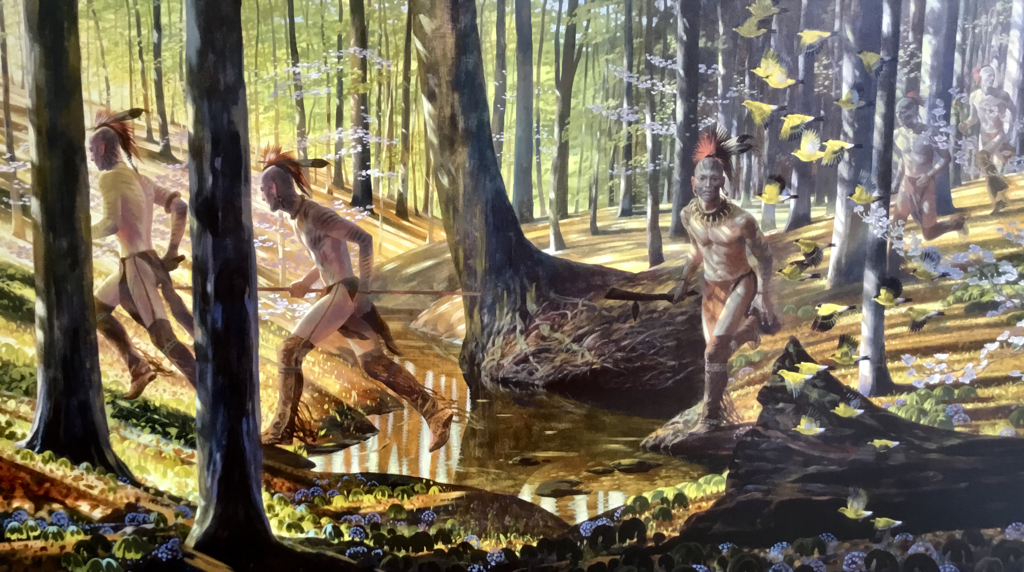

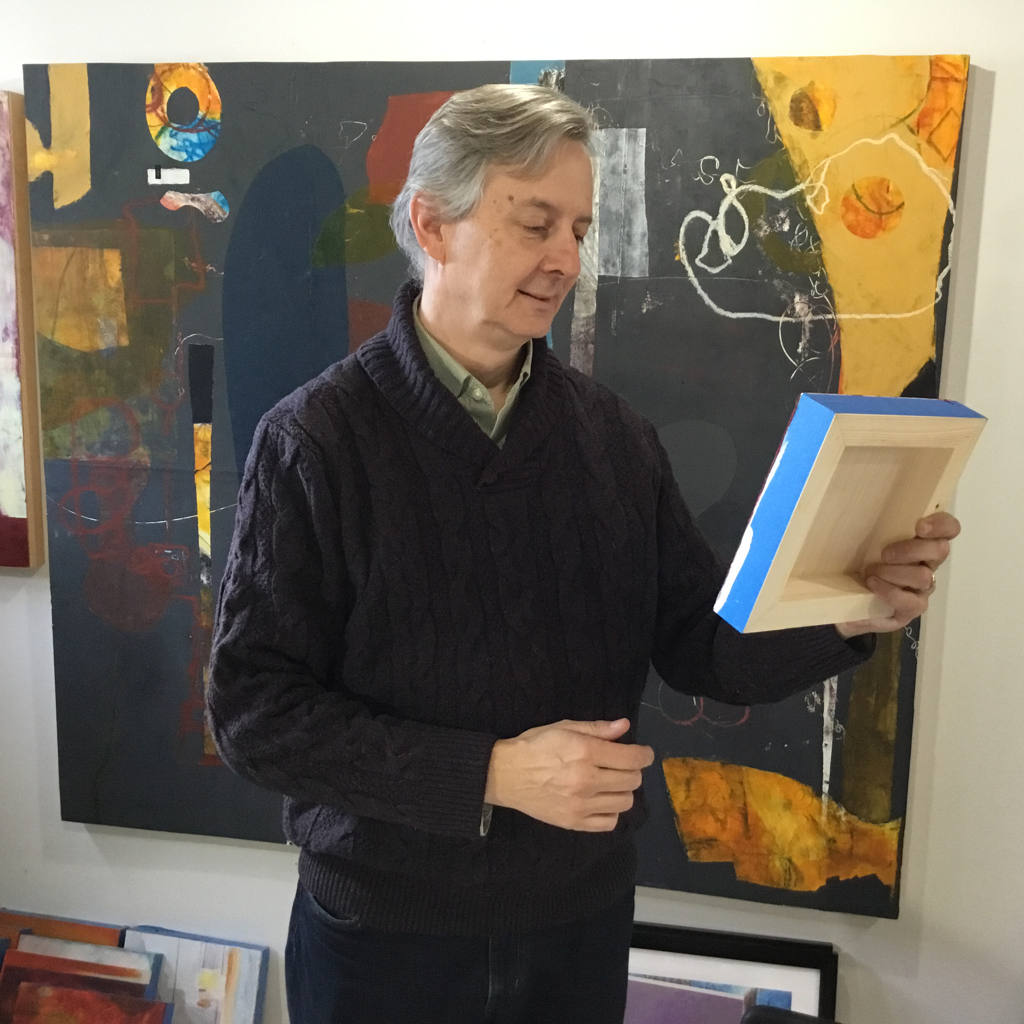

There is no mistaking the work of Bryan Haynes for that of any other artist. His style, shaped by 20 years as a professional illustrator, presents skillful renderings of the human figure, thoughtful use of perspective, and a full color palette. But what makes his work even more distinct is his subject matter - the people, land, and history of Missouri river country. “I’ve got my medium. I’ve got my vocabulary in paint. Twenty years ago I left behind how to paint something. Now it’s about what to say. There are so many stories to tell about this region. It’s limitless. I have more ideas in my sketchbook that I could ever get to.” The figures in Hayne’s paintings - farmers, pioneers, workers, Native Americans - are heroic in the ways we hope our ancestors might have been. And their actions are woven into the patterns of the land itself. Because the rivers and bluffs, fields and hills are major characters in his paintings, in constant interaction with the people who live among them. You can feel the muscle, bone and breath of the land in Bryan Haynes’ vision of our region. With acrylic paint and canvas he tells stories that reconstruct the history of America’s frontier in ways that approach mythology. A group of running Indians is accompanied by a cloud of parakeets (once prevalent in the Missouri River region). His farmers and pioneers wield tools with vision and purpose. A young woman strides across the plains like a goddess. If these painting don’t depict daily life as it truly was, it captures the way it should have been. The way we would like best to remember it. They present American archetypes that touch us. “I like to start with gestures that are strong and heroic, because those people were strong. Maybe I’m creating theatre on the canvas - a tableau. I want the beholder to look at my painting and not see realism, but join me in this land that I have created.” This past year Bryan and his wife Petra moved from their home in the woods outside Labadie to Washington, Missouri, where he established a galley and studio in a historic building downtown. For the first time in years he has daily contact with the people who appreciate his work. “I’ve noticed that working in the studio when the public has access, I’ve had to start explaining what I’m doing, and I’ve never had to do that. And it’s been an interesting exercise, because to verbalize intuition is hard for some artists, like me, to do. In the past it was always just a matter of - ‘look at the painting, there it is.’” Borrowing from his experience as a commercial artist, Haynes approaches each piece systematically and with a clear idea of where he’s going with it. Typically a painting begins with a story, which he might have read, heard from an elderly neighbor or received as a commission. The first step is to research that story in depth so that whatever he paints is historically accurate. Then he creates a series of small sketches depicting details, first in black and white and then in color. The trick, he says, is to keep the dynamism of those small sketches alive and working together as he integrates them on the canvas. Recently a collection of those sketches were presented in exhibition at OA Gallery in Kirkwood. “I think art has to have craftsmanship. That has to be part of it. “I want the paintings to have depth and meaning in the things that are in them. The sketches start with the armature of geometry, and that undergirds the painting, and hopefully the feeling. When I have diagonals, I hope there is a feeling of dynamism and maybe even aggression. When it’s horizontal, there’s quiet and serenity. “I think in sculptural terms. Light and shadow on a form, how to make it round. So, when I’m painting, I already see it in my head, so I just need to bring it out, bring it to fruition.” Haynes tells of how, when he attended school, it was commonly assumed that that illustration and fine art were poles apart and that representational art - and the skills necessary to create it - were under appreciated. He believes that is changing. “I see my figurative storytelling as part of that movement,” he says. “I’m in search of beauty. In form. In color. In storytelling. Viewers of my paintings are invited to come along for the ride. Just come with me to this place, and we can enjoy it together.” You can see more of Bryan Hayne’s work in “New Regionalism: The Art of Bryan Haynes” by Karen Glines and “Growing up with the River” by Dan and Connie Burkhardt, or visit his website at artbybryanhaynes.com Over the past twenty years the focus of Mark Witzling’s work has evolved from the figurative to abstract. It’s a creative shift that has offered him endless possibilities for experimentation in his paintings. “I love abstraction. It’s freeing. I paint realistically as well, but abstraction uses all of the tools and techniques that you use when you do realistic painting, but it frees you from having it look like something else. It’s all about what you’re trying to express from the inside and bring that out.” About eight years ago he discovered the technique of mixing cold wax with oil paint. The wax, which is soft, almost creamy, mixes easily with the oil and can be brushed on to a canvas. And the combination allows - particularly for an abstract painter - a wide variety of opportunities and challenges. Today it’s his medium of choice. “Oil and cold wax is all about building up layers and layers and layers of paint and then excavating back down and building up more layers. There’s this whole give and take, so maybe this painting is about layers of warm over cool and then cool over warm, or about value contrast, or a limited palette, or about lines and marking. So, it’s not just totally free and random. I have some sense of what I’m trying to do with it.” The overall concept of the painting might be something very abstract - like a reflection on memory. Or an inspiration from a thought or feeling he has experienced in the course of daily life. But most interesting to Witzling is the technical challenge he sets up for himself in each painting, which may or may not be consciously perceived by viewers. “For the most part, the drivers for me are color first and then shape next. And after that it’s a mixture of mark making and texture and line, and I’ll experiment with different things. “When I’m painting, I’m not thinking of how the viewers is going to react to the painting. That comes later. I think the payoff comes when somebody asks you about the work. They might see something in the painting - a landscape, the ocean or a person - that had nothing to do with what I was creating - but that doesn’t matter. The fact is, the work engaged them at some level. It elicits some kind of response.” Witzling offers an observation about his own work flow that might serve as a valuable piece of advice for any artist who encounters frustration at some point in the creative process: “It’s important not to try to fine tune the work too early. With oil and wax painting when you’re building up all these layers, it’s really easy to fall in love with the early layers - a color or a portion of the canvas that you don’t want to change - but that’s when you start to falter because you’re putting constraints in the works. You need to be able to cover up something you really love to get to the next level in the painting.” “There’s always an ugly stage in the middle of the work. There are the early stages when you’re getting a foundation. And then there’s sort of an ugly stage, and then the work starts to appear and evolve. Then you build up those final layers, experimenting and sometimes making mistakes. But you just keep on going.” “When I’m painting in the studio, it’s the only thing that I do just for me. It’s my time. It’s honest, and what I mean by that is that whatever ends up on the surface - for good or for bad - I’m the only person who can do that. Other artists can do things that I can’t do, but this is mine. And that’s thrilling - to create something that no one else can do. It’s the only thing that I can do that no one else can.” Visit him at www.markwitzlingart.com

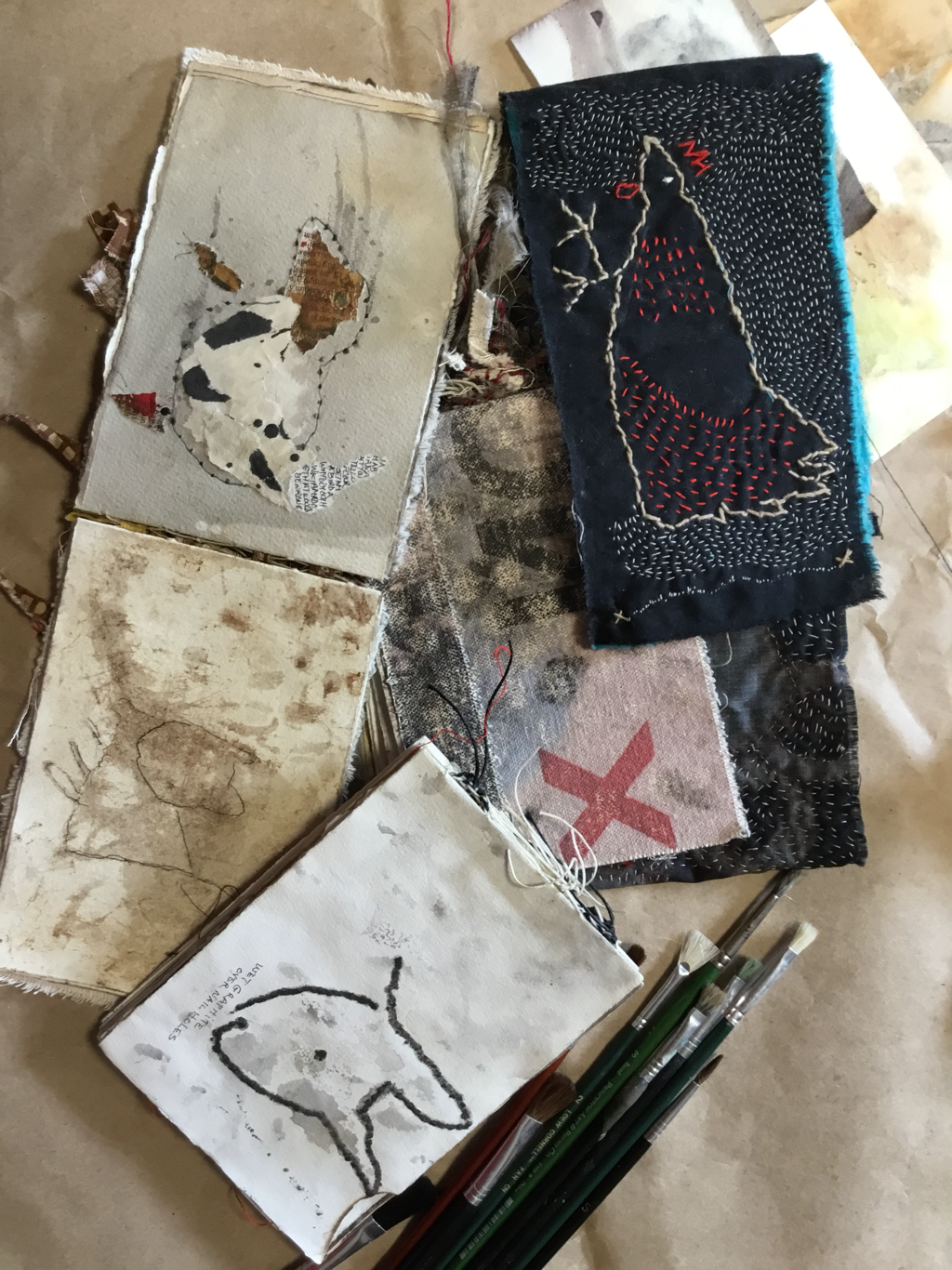

Suzy Farren creates art from just about anything - leaves, fabric, pieces of paper, interesting objects she finds in the street. Because for her it’s about finding things that somehow belong together - then arranging them and rearranging them, marking them with paint or ink, chalk or thread - until they combine to complete her vision of what they are meant to be. “I love scraps. Everything I do has scraps in it.” She spreads out a collage across the table in her studio. “So this is a piece of Japanese fabric. This is fabric I printed. This is an old pharmaceutical prescription. Here’s a scrap of my father’s handwriting. “I never know how a piece is going to turn out. I never have a finished piece in my mind. I just know that when I add marks and color and pieces of paper, this collage is interesting.“ Farren spent most of her professional life as a writer in the corporate world. And though she still has a love for words and even includes them in her collages and creations, she sees the process of writing and creating her art as essentially different. “It is the anti-writing. When I’m writing, I’m inside my head, thinking. But when I’m creating something, I’m not thinking. I’m making my marks, I’m making a mess. I’m just putting stuff down. I’m not thinking, ‘Oh, I’m going to have this picture.’” That word - marks - comes up a lot when she talks about creating art. “I like making marks,” she says, “with a piece of crayon, a piece of chalk, a paint brush, a stitch, whatever.” It’s as if after working for years with words, she realized that even though they could touch other people, she could never really touch them. But the marks, the fragments and scraps are all tactile - things she can feel. “Touch is a really important part, whether I’m stitching or doing a piece on canvas. My hands always get really involved. And I especially like working with fibers. I like making books. Books are just so intimate, you hold them in your hand, you touch them.” Her books have a charm all their own. They are indeed books, - not like any books you’ve ever seen, but wonderful to touch. And playful, as if they invite you to stop thinking and join in the fun. Farren picks up a piece of fabric bearing bold marks in ink and paint. Glued on the surface is some object - crescent shaped, metal, rusty and jagged. It’s a part of an automobile she found in the street while taking a walk. “And it fits perfectly,” she says. “And this happens all the time. These pieces just show up because you need them.” It’s funny, she says, how creating art can reveal things about ourselves we would otherwise never discover. She tells the story of how she grew up in New Jersey on 84 acres of farmland where her family lived in an old stone house. She was an only child and there weren’t many kids around, so she spent large parts of her day bouncing a ball against the side of the house. “And so if you look at my palette, it’s the stone walls of the old house. I’m drawn to certain colors and certain textures. Everything I do is sort of brownish, and it’s the color of stones. I discovered that over the years as I created this work.” Just a glance around her studio leaves no doubt that she has no shortage of material for future projects. Piles of scraps, found objects, fabric swatches, pieces of this and that. All grist for her creative mill. Farren warns against “the critic inside our heads”, because, she says, “if we’re not careful it can keep us from being creative. Anything perfect makes me nervous. My marks, my stitches are imperfect - deliberately. “So maybe these are my stories. These little pieces. They just all tell a story. So these marks, I just love them. It’s intuitive. It’s organic. At this point I don’t know where I want to go with it. I just want to go day by day, doing what I love. I do it because I really have to do it and I love it.” Visit her at suzyfarren.com

The original plan was modest. Doug Auer and his friend Jim McKelvey would teach classes in glassblowing to buy a place where they could indulge their love of glass art. It worked. They bought a cluster of abandoned buildings on Delmar and opened shop - holding classes, selling glass and developing their skills. Fifteen years later, Third Degree Glass Factory has grown to be a major fixture of the St. Louis arts scene - attracting students, artists and the curious. Hundreds of pieces of art are available to purchase in their gallery. Third Friday’s are a major draw - offering music, food and drink, and glass blowing demonstrations. Third Degree has also created a community of artists where there was none, putting St. Louis on the national map as a center for glass art. Today Auer continues to develop his craft in addition to running the business side of Third Degree. He’s long had a fascination with the medium. “It’s so unique. It’s transparent. It’s translucent. It transmits light. It reflects light. It’s shiny but it’s soft. It’s cold. It’s hot. Watching it being made is unbelievable. “I also like that it’s this combination of art and science. Working with a fluid, molten material involves a lot of thought. After a while you just sort of feel it, but the processes behind the creation fascinate me. I love the physics of it.” Part of the attraction he attributes to his own lack of patience. “I like the spontaneity of glass. Creating it is such a fast process, as opposed, say to making ceramics. Inside a 20 to 30 minute session, it’s start to finish. There’s no stopping and coming back later, and for me that works really well.” The art is created in a variety of ways. Much of it takes shape through the traditional methods of blowing into molten glass, then turning, shaping and even twirling it into bowls or vessels. Other pieces are created by cutting and fusing pieces of glass into artist works or practical items like glass tiles or cheese platters. One section is dedicated to flamework, where artists produce small items like beads for jewelry. “Glass blowing has been around for so long, much of it is rediscovering techniques that have been forgotten,” says Auer. It’s not surprising that a community of artists would eventually emerge . As he points out, working with glass is fast, hot and potentially dangerous. “The art of glass blowing is a team sport, so we wanted to build a pool of people who could work together. “In the beginning there were just three or four of us making glass, and today we have over two dozen artists making their art and exhibiting in the gallery. We have a team of almost thirty artists teaching classes all year, many who got their start here taking classes.” Auer’s work has evolved over the years as he experiments with techniques and discovers new qualities of the medium. “Right now I’m into making these translucent, colored, simple teardrops, shaped as if by gravity. There’s something really nice about the simplicity - really thick glass with a layer of transparent glass and an interior of color that sort of floats in there.” You can see an example of one of his large installation pieces in the lobby of Scape Restaurant on Maryland Avenue in the Central West End - a complex arrangement of smaller glass pieces, forming a sculpture that impacts the space it occupies in varying and unpredictable ways. But even a small piece can have the same effect, making glass different from other types of art. “Any time there’s glass, if sunlight comes through it, not only does the glass glow, but it creates what I call colored shadows on the floor and on the wall. And it’s amazing. And with its 3-dimensionality, you can walk around it and enjoy it from a variety of perspectives.” The best way, of course, to understand the effects of glass is to experience it directly. Auer says there are very few “Don't’ Touch” signs in the gallery. “We want people to pick it up, feel it, experience it through touch as well as sight.” And at Third Degree visitors can watch the entire creative process - from molten glass to finished product. And after bringing the art of glass to the public for fifteen years, Doug Auer hears one comment more than any other.

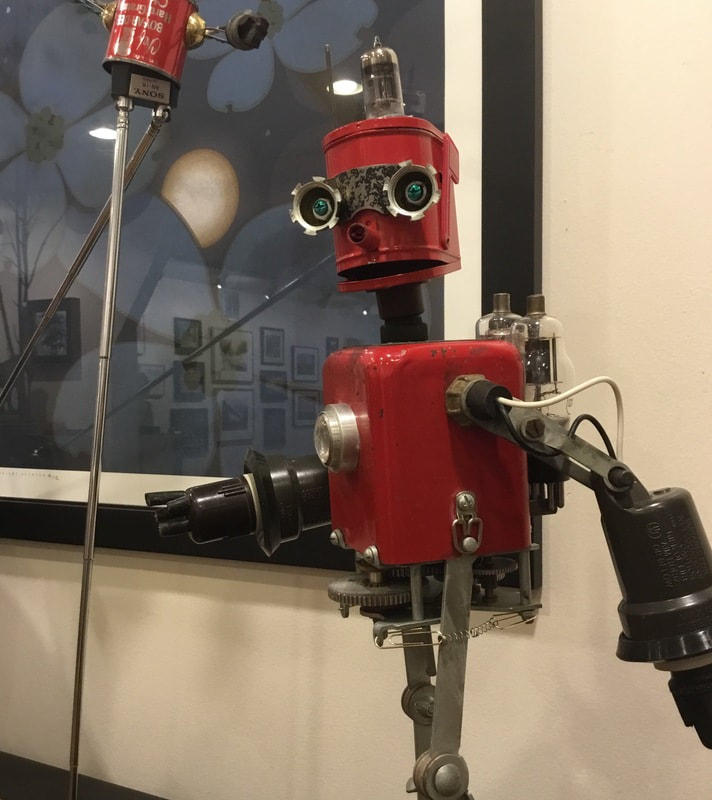

“When people visit us, the word we hear the most is ‘amazing’, so we have adopted it as our unofficial motto - ‘Glass is amazing.’ “We’re here to make amazing experiences happen with glass. That is our mission.” Visit Third Degree Glass at www.thirddegreeglassfactory. Art, for Shawn Cornell is a natural extension of his strong sense of curiosity. About everything. “As an artist and as a human being, I’m always finding interesting things,” he says. “Whether it’s music or cooking or writing, there are things that just intrigue me, and I need to try those things.” Shawn is well known for his plein air works, but he produces prints, pottery - and even a collection of robots made from found objects. He’s planning on learning how to work with bronze and blow glass. There are apparently no limits to the materials he is willing to incorporate into his creative projects and no hesitation in learning how to master them. Shawn’s manner is low key, but it’s clear that he thoroughly enjoys what he does. His artistic style reflects his approach toward most things. “Quiet. Calm. I’m not going to yell at you. I’m not going to use bright, bright colors. I’m not going to bang the drum at you. It’s more as if I’m going to whisper poetry.” His plein air works describe the quiet beauty of nature and capture moments in ways that make you feel that this place exists for the moment purely for you. The light. The time of day. The weather. It’s all there, whether in a patch of prairie, a lily pond, the bend of a stream, a hillside of flowers or an architectural detail on a farm. Shawn has worked as a full-time, independent artist for over ten years and values the freedom of his creative life. “I was a graphic designer for 20 years, and for those 20 years everything I did had to be approved by someone else. And after I got out of that field, I promised myself that I am not going to be submitted to that process. I’m going to go out and paint something that I enjoy and just hope that somebody else gets something from seeing it.” And that love of freedom extends to how he paints. “You don’t want to be a servant to what’s in front of you. Nature’s wonderful, but she doesn’t always have the best answers to what should end up on a canvas. You as an artist need to do your best to create a pleasing image that’s going to be represented on a wall.” He talks about the process of actually going into the countryside, finding an interesting scene and capturing it on canvas. For Shawn it involves the challenge of considering the relationships between “reality” and art, the artist and the viewers. “I learned an important lesson in art school - ‘indicate, don’t duplicate’. If you include everything, you eliminate that interaction between the viewers and the piece. You’re telling them everything as opposed to letting them fill in a few things, letting them interpret and be a part of the image. “The difference between plein air painting as opposed to working with a photograph is that the photograph is cropped. If you go out there and paint plein air, your expanse is everywhere you look, and it’s easy to be overcome, so you have to simplify it. So my job as an artist is to edit it so it makes sense to me and so hopefully have it make sense to people who view it.” Every plein air painting comes with a written description of the circumstance surrounding its creation. If you talk with Shawn at a gallery or an art show, he’s eager to talk about the temperature, the weather, and what happened before and after he painted a scene. Because paintings are stories, and stories offer yet another way to share the creative experience. And for Shawn it’s important to communicate the very real experience of being in that particular place at that particular time. As he states on his website, “If you see snow in the painting, it means the artist was standing in snow. If you see rain in the painting, it means the artist was getting very wet.” But even the most energetic artist hits the occasional creative wall, and Shawn has his own solution. “If I’m out painting for a week and start to get creatively blocked, in order to clear that up, I shift to pottery. And it’s a mind shift. I go from 2-D into the 3-D and it completely clears my mind, so I have to start rethinking how things are done.” Much of his ceramic work is reminiscent of the Arts and Crafts and Art Deco movement of the early 20th century. His prints are often based on his plein paintings, which gives him the opportunity to interpret his own works from oil to graphic. From working in the weather and elements to working in a studio. You might see an occasional reference as well to WPA posters of the late 1930s. And though “Robots” might not be a genre on their own, Shawn has a collection of mechanical men he has assembled from interesting items he finds here and there. “When it comes to my robots, they’re just found objects that I started putting together, and it’s like a puzzle putting them together. And they’re not mean robots. They’re not scary. You might want to go over and shake their hand. And that’s the kind of person I am, and I think that’s what comes out in my art.” And so there are many approaches we can take to share the vision of Shawn Cornell - and a very wide variety of media in which that vision lives.

“Yes, they are all very different, but if you put them all together, there is a unity within them. If you put one of my paintings next to one of my prints, next to my pottery, there is a harmony there. Once you put them together, you can see a common hand.” Visit his website at mshawncornellstudio.com Welcome to my brand new blog. I’m excited about it. It’s definitely something new for me. But it’s not a big leap from what I’ve been doing the last several years - producing programs about the arts and the people who make them possible.

In January of 2017 I retired from St. Louis Public Television after more than 30 years - to produce arts-related television programs as an independent producer - and pursue my love for making pictures with paint. What I’d like to do with ARTsy STL is similar to what I did with the weekly TV show “Arts America” - introduce people who populate our local arts scene - the leaders of arts institutions, curators, gallery owners, philanthropists, and - above all - the artists. Because these are the people who make St. Louis the vibrant Art Town that it is. These are the people who broaden the range of our experiences and bring life to our community. They touch us. And it’s worth knowing them. So please, drop in when you can. Your feedback and suggestions are always welcome. Patrick A first impression of Henryk Ptasiewicz - whether meeting him in person or viewing his art - is that this is a guy who is serious about whatever he does. It’s there in his bold brushstrokes, his choice of colors. He expresses it with a dash of humor, but he’s serious when he talks about art - how to make it and how it relates to the real world of our daily lives And he makes a damned serious cup of coffee. For Henryk, being alive on the planet earth - and translating that experience through art - is the primary focus of every day. His studio in the old Koken barber chair factory in South St. Louis bursts with paintings, sculptures and whimsically constructed objects from floor to ceiling. “The difference between me and a lot of painters is, I don’t wait for the muse to bite me on the bum. On a good day I’d spend eight hours drawing, eight hours painting, eight hours sculpting. But you can’t live like that.” Henryk was born and raised in an industrial town in the North of England. His father fought with the Polish Free Air Force before moving to England to join a Polish Squadron of the Royal Air Force. He studied at St. Martins School of Art in London and worked as a graphic designer, creating album covers, paperback book covers, “whatever it took to make a living”, and then as a commercial fiberglass designer and sculptor. In 1984 he met artist Robert Lenkiewiez, who impressed upon him the power of art to change how we see the world. In 1999 Henryk moved to the United States, determined to make his living as a painter. He quotes Lenkiewiez to sum up his own no-nonsense approach toward creativity: “All an artist needs is two brushes - one to paint and the other to brush his teeth.” Henryk’s paintings - whether portraits, plein air, abstract or fantastical - exude energy. He wants to get it down on the canvas as quickly as possible - while pulling viewers into the content in ways that are hard to resist. “I haven’t got any patience. I so much want to move on to the next thing. I need to get it down with attitude. If you look, there are certain elements of my paintings that are not finished. And the reason is, the way the eye works. You don’t see so much in focus. Most of what we see are impressions. I work backwards from that. I start out with an impression and then I’ll focus on the bit that I want you to look at.” But if you want to get into a conversation with Henryk about technique, you won’t get far. “Technique,” he says, “doesn’t matter. It’s not about technique. It’s about intent. All you’re doing is putting paint on the canvas, and you can do it with a toilet brush if you have to. You can do it with your fingers. If you’re going to sit there and talk about technique, I’ll leave the room. I’ll fall asleep.” But Henryk’s opinions on technique are best understood as the thoughts of an artist who has mastered the elements of his craft to the point where he doesn’t needto think about them consciously anymore. Think Charlie Parker on breathing techniques. Or Thelonious Monk on fingering. “You don’t look at the beauty of the brush stroke. It’s about the object - the narrative - of the painting. I get you to respond emotionally if everything works. It’s unconscious. It’s subliminal. That’s what an artist can do.” Favorite subject? “Everything! I haven’t got one thing that I prefer over anything else. But there’s nothing more interesting than people.” In fact, portraits cover a good portion of his studio walls. “Everybody’s got a story. If you’re sitting for me, we’ll be talking. I want to know about you. I find that appealing.”

Foremost, Henryk Ptasiewicz wants to create art that is “more than just a pretty picture for your aunt’s wall.” Art for him is a means to an end - a way to explore - without boundaries or limits, and present whatever he finds in ways that might change us. “I’m giving you permission to stare. Now you’re talking about the power of art. You can have any reaction you want. You can be visually appalled or enthralled. “I want you to come and see the world through my eyes. There are seven billion people on the planet and only one of me. So, yeah, this is my viewpoint. That’s all I’m asking. We live in this incredible place. We just have to take our blinders off and see it.” |

Patrick Murphy has worked in St. Louis radio and television for the past forty years. He has produced a variety of arts-related programs for for St. Louis public television, including the series "Arts America" and "Night at the Symphony". He currently serves on the Webster Groves arts commission and is an aspiring water colorist.

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed